This brief introduction is adapted from material in Joseph Fitzmyer’s A Guide to the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jonathan Campbell’s Deciphering the Dead Sea Scrolls, Alison Schofield’s From Qumran to the Yahad, and James VanderKam’s The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls. These volumes are highly recommended for a more detailed and thorough introduction to this subject.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls stands as one of the most remarkable and important archaeological finds of the 20th century. These ancient manuscripts, hidden for two millennia in desert caves overlooking the Dead Sea, provide an unprecedented window into religious life and traditions that predate both Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism.

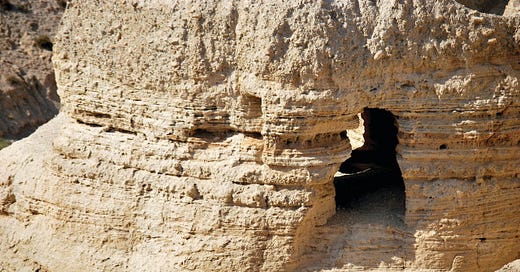

Discovered between 1947 and 1956 in eleven caves near Khirbet Qumran on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, which borders Jordan, the West Bank, and Israel, by Bedouin shepherds. The first cave, now known as Cave 1, was found in 1947 by a young shepherd named Muhammad edh-Dhib. The scrolls date back to the last few centuries BCE and first century CE and consist of nearly 900 manuscripts, written mostly in Hebrew, Aramaic, and some in Greek.

The scrolls come from a pivotal time in Jewish history known as the Second Temple period. This began with the rebuilding of the Jerusalem Temple following the Babylonian exile and ended with the Temple's destruction by Rome in 70 CE. The religion of this period evolved significantly from pre-exilic Israelite religion, on to the developments that just pre-dated early Christianity and the Rabbinic Judaism that developed in the following centuries. The scrolls fill a knowledge gap about Jewish religion, thought, and social dynamics in this formative period and have been invaluable resource to scholars immediately following their discovery. The scrolls can be divided into three main categories:

Known works that predate the scrolls' discovery. This includes books from the Hebrew Bible, with the notable exception of Esther, as well as deuterocanonical and pseudepigraphal works such as Tobit, Sirach, Jubilees, and 1 Enoch. The scrolls provide the earliest surviving manuscripts for many of these works, predating previously known copies by up to 1000 years in some cases.

Previously unknown works that were likely in circulation at the time. These include texts like the Genesis Apocryphon, an Aramaic elaboration on stories from Genesis. While unknown before the 20th century, they probably had wide circulation in ancient Judaism.

Sectarian works likely authored by the Qumran community itself. With the possible exception of the Damascus Document, these texts like the Community Rule and War Scroll provide a unique window into the beliefs and practices of an ancient Jewish sect with probable connections to a group known as the Essenes.

The ruins at Khirbet Qumran above the Dead Sea were first excavated from 1951-1956. Based on archaeology, pottery, and coins found at the site, the buildings were inhabited from the 2nd century BCE to 68 CE, when they were destroyed by the Romans. They outline a pious, isolated community awaiting an imminent apocalyptic battle between good and evil. The site features a scriptorium for writing scrolls, thousands of pottery shards, and communal facilities like aqueducts, cisterns and dining halls that could support about 200 residents. However, they likely lived in tents and caves nearby.

The scrolls that this community produced have been labeled using a standard system to keep track of the huge number of fragmentary manuscripts. The labels identify the cave where the scroll was found, the type of work, the copy number if there are multiples, and sometimes the language. For example, scroll 1QIsaa (also known as The Great Isaiah Scroll) indicates the cave number, the related text, and the designation that it was the first copy found. Other notable scrolls include: 1QapGen (the Genesis Apocryphon), 1QTLevi (from the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs), 1QH (the Hodayot or Thanksgiving Hymns), 3QCopScr (the Copper Scroll), and 4QMMT (the Works of the Law).

In many instances, the scrolls largely match the traditional Masoretic Text, demonstrating the careful preservation of these texts over millennia. For example, the Isaiah Scroll from Cave 1 is nearly identical to the Masoretic version, aside from minor spelling differences and a few missing pieces.

However, the scrolls also contain intriguing differences that point to a period of textual fluidity before Hebrew Bible books were standardized. The Jeremiah scrolls exhibit significant variations compared to the Masoretic Text, including a different chapter order. The publication of divergent manuscript evidence like this fueled debate about which family of biblical manuscripts most accurately represents the original texts. Some of this is reinforced, and even complicated, by other text families found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, including those which align more with the Greek Septuagint (such as 4QDeut-q, 4QSam-a, 4QJer-b, and 4QJer-d) and others that align with certain readings found primarily in the Samaritan Pentateuch.

Several scrolls that were found here are also notable for their use of a unique method of interpretation and commentary known as pesher, often translated as "interpretation" or "solution" from Hebrew. These texts include commentaries on various scriptural passages, often seeking to uncover hidden or deeper meanings behind the words. These texts follow a unique format: they start by quoting a verse from the Hebrew Bible and then proceed to explain its hidden significance, typically in relation to events or figures of their own time and in the context of the community writing it. The pesher writings often employ a dualistic worldview, where events of the past and prophecies of the future are understood as having direct correlations. Pesher is also noted by scholars as being an early version of what developed into midrash in Jewish and Christian reading practices.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have profoundly impacted scholarship on early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. Although an isolated Jewish sect, the scrolls provide context for understanding the diverse religious environment that in many ways pres. Some scrolls elucidate Jewish messianic expectations and apocalyptic ideas that are similar to early Christian beliefs. By situating New Testament literature within that contemporary expression of Judaism, the scrolls help explain how Christianity emerged from Second Temple religious practices and social dynamics.

Additionally, the scrolls fill a knowledge gap about post-biblical Jewish religion preceding Rabbinic Judaism. Though at times diverging, the scrolls illuminate possible precedents and parallel developments to the rabbinic traditions codified after the Temple's destruction. By shedding light on Jewish thought right before the rise of Rabbinic Judaism, the scrolls enable deeper investigation into how rabbinic ideas emerged and developed.

The discovery of the scrolls was truly momentous and their impact cannot be understated. No study of Jewish and Christian history is complete without integrating the evidence and insights gleaned from these texts.