The Targums and Biblical Traditions

The Intersection of Development, Innovation, Text, and Tradition

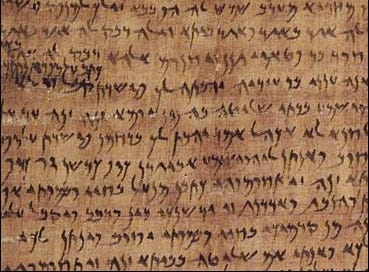

The Aramaic Targums (What is a Targum?) provide an important point of contact for how biblical traditions grew and expanded throughout the Second Temple period and beyond. Studying these texts and the traditions they represent in continuity with other related traditions reveals a complex intertextual matrix of theology, history, and more.

Dating the Targums, particularly the underlying traditions that the Targums represent, is a complicated task for scholars. While there is a more general agreement on the dates for the written texts, questions of dating are made more complex because in several places these texts may reflect either oral or prior written traditions that are centuries older than what was eventually preserved. These known and earlier traditions come from diverse sources such as the Septuagint, the Deuterocanon, the New Testament, Greco-Roman authors, and other notable Jewish authors such as Philo and Josephus.

An excellent example of this phenomenon is found in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan's retelling of the Red Sea crossing in Exodus 15:19 with a literary expansion:

The children of Israel went on dry ground in the midst of the sea. There sweet springs sprang up, as well as fruit trees, green plants, and choice fruit at the bottom of the sea. (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Exodus 15:19)

A remarkably similar tradition of this kind of expansion is also found in the deuterocanonical text known as the Wisdom of Solomon:

… where water stood before, dry land appeared; and out of the Red Sea a way without impediment; and out of the violent stream a green field. (Wisdom of Solomon 19:7)

What makes this specific example particularly noteworthy, though, is that both of these readings appear to be based on a detail added to the book of Isaiah:

… the one who made his majestic power available to Moses, who divided the water before them, gaining for himself a lasting reputation, who led them through the deep water? Like a horse running through the wilderness they did not stumble. (Isaiah 63:12-13)1

While Isaiah’s additions of the horse and the wilderness are very likely just a literary metaphor, later traditions represented by both Wisdom of Solomon and the Targum appear to have read it more literally and expanded further upon it, as it suggested to ancient interpreters that the Red Sea had also been miraculously turned into a grassy valley rather than merely parted.2 In this case we can trace the development of a tradition from the Hebrew bible, through the prophets, and on to the Deuterocanonical and Targum texts. This is evidence that even though the Targum is technically “late” from a written standpoint, the tradition that lies behind it is much older.

Two New Testament examples of this same phenomenon can be found in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Starting in Matthew 26, we see a well-known statement attributed to Jesus during his arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane:

… one of those with Jesus grabbed his sword, drew it out, and struck the high priest’s slave, cutting off his ear. Then Jesus said to him, “Put your sword back in its place! For all who take hold of the sword will die by the sword …” (Matthew 26:51-52)

Targum Jonathan on Isaiah includes a similar expansion based on Isaiah 50:11:

The Holy One, blessed be He, answered and said unto them: Behold, all of you who stir up a fire, and lay hold on the sword; go and fall into the fire which you have stirred up, and die by the sword, which you hold on to. This is my Word to you: You're heading to your own destruction. (Targum Jonathan on Isaiah 50:11)

Look, all of you who start a fire and who equip yourselves with flaming arrows, walk in the light of the fire you started and among the flaming arrows you ignited! This is what you will receive from me: You will lie down in a place of pain. (Isaiah 50:11)3

New Testament scholar Bruce Chilton argues that while there is no direct literary connection between Matthew and this Targum, the degree of similarity between Matthew and the Isaiah Targum demonstrates that there is most likely a shared tradition behind both with regard to “dying by the sword” a statement not found in the Hebrew text of Isaiah.4

The Gospel of Luke contains another text tradition connected with a Targum, this time the Targum on Psalm 91:

You need not fear the terrors of the night, the arrow that flies by day, the plague that stalks in the darkness or the disease that ravages at noon. Though a thousand may fall beside you and a multitude on your right side, it will not reach you … You will subdue a lion and a snake; you will trample underfoot a young lion and a serpent. (Psalm 91:5-7, 13)

Be not afraid of the terror of demons who walk at night, of the arrow of the angel of death that he looses during the day; of the death that walks in darkness, of the band of demons that attacks at noon. You will invoke the holy name; a thousand will fall at your left side, and ten thousand at your right; they will not come near you to do harm … You will trample on the lions’ whelp and the adder; you will tread down the lion and the viper. (Targum Psalms 91:5-7, 13)

What we find in this Targum tradition is an expansion of the more general details of danger and disease in the Hebrew Psalm into very specific imagery of demons and angels. The Gospel of Luke incorporates this same expanded imagery into Jesus’ statement of spiritual authority to his disciples and connects the demonic imagery with the existing animal imagery:

So he said to them, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven. Look, I have given you authority to tread on snakes and scorpions and on the full force of the enemy, and nothing will hurt you …” (Luke 10:18-19)5

Craig Evans notes this relationship: “Jesus assures his disciples that he has given them the ‘authority to tread on snakes and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy’. Jesus is alluding to Psalm 91:13 (‘You will tread on the lion and the adder’), but as this passage was interpreted in pseudepigraphal and targumic tradition. The demonic interpretation of Psalm 91, attested [in the Dead Sea Scrolls] (cf. 11Q11), also clarifies the function of Psalm 91:11-12 in the temptation narratives …”6

What Evans highlights is that this specific interpretation of Psalm 91 can be found in no less than three distinct and later traditions: the Dead Sea Scrolls, New Testament, and Targums. The Targum has again preserved a tradition that is centuries older than its written text.

Perhaps the most complex example of the multiplication of traditions behind a later text are what lies behind the Pauline statement found in 1 Corinthians 15:

For I passed on to you as of first importance what I also received—that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the scriptures. (1 Corinthians 15:4)

Scholars have pointed out for centuries that the attribution of scripture to the phrase “raised on the third day” is not found in nor has any direct relationship with the Hebrew bible. Joseph Fitzmyer’s commentary on 1 Corinthians goes so far as to label this specific passage as “problematic”.7 Many ideas have been proposed as a possible referent for this clause, but perhaps this is another case where multiple traditions intersect? The original Hebrew passage in Hosea, which is typically read as relating to the restoration of the nation of Israel in exile8, states:

Let’s return to the Lord. He himself has torn us to pieces, but he will heal us! He has injured us, but he will bandage our wounds! He will restore us in a very short time; he will heal us in a little while, so that we may live in his presence. (Hosea 6:2)

Many modern translations, including the NET above, will often render the literal “two days …. three days” into the idiomatic “very short time” and “in a little while” which often obscures any intertextual connection. However, the Septuagint of Hosea translates it very literally:

After two days he will make us healthy; on the third day we will rise up and live before him and have knowledge. We will press on to know the Lord; we will find him ready as dawn, and he will come to us like the early and the latter rain to the earth. (LXX Hosea 6:2-3)

Here, any trace of a Hebrew idiom is rendered into a much more literal Greek translation emphasizing the “third day” as well as using much more traditional resurrection language. However, even if this resurrection language is still somewhat metaphorical, the targum of Hosea draws it out much more explicitly:

He will give us life in the days of consolations that will come; on the day of the resurrection of the dead he will raise us up and we shall live before him. And we will diligently seek to know the fear of the LORD, like the morning light that shines brightly on its path, and may He give us strength, like the rain that strengthens the earth. (Targum Jonathan on Hosea 6:2)9

What may be behind the Pauline reference to resurrection on the third day in 1 Corinthians 15 is the intersection of three different traditions - Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek - cumulatively into a new tradition thus referenced as “scripture”. If this is indeed the case, then it would serve as a possible explanation for an otherwise enigmatic Pauline reference. John Cook summarizes all of this thusly, “... there is little reason to doubt that Hosea 6:2 is a reference to the restoration and healing of Israel, and not the resurrection of the dead. In later interpretation, however, probably beginning with the LXX and culminating in the targumic translation, the text was taken to describe the resurrection ... This implies that early readers of the LXX could have interpreted 6:2 to refer to resurrection, and this is reflected in later Jewish interpretation of the passage ...”10 The net result of this is that 1 Corinthians would ultimately reflect a literary dependency on a cumulative tradition that would otherwise be made explicit in a Targum to the Hebrew prophets.

A final example is the appearance of the apocryphally named magicians Jannes and Jambres in 2 Timothy:

… just as Jannes and Jambres opposed Moses, so these people—who have warped minds and are disqualified in the faith—also oppose the truth. (2 Timothy 3:8)

This pastoral epistle draws on these notable characters in the context of a discourse on immoral behavior and to the audience would perhaps represent its epitome. However, the specific detail of the names of these Egyptian magicians are nowhere to be found in the Hebrew text. Along with their inclusion in the New Testament we also find them in later traditions represented by the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Targums, Rabbinic texts, and even in Greco-Roman historians such as Pliny the Elder.11 Targum Pseudo-Jonathan injects them into the Exodus narrative directly:

… he sent and called all the magicians of Mizraim, and imparted to them his dream. Immediately Jannis and Jambres, the chief of the magicians, opened their mouth and answered Pharoh. (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Exodus 1:15)12

Pete Enns highlights how these names originated as part of the broader interpretive traditions of Second Temple Judaism before being incorporated seamlessly into 2 Timothy: “This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the ‘interpreted Bible.’ What earnest Bible readers think the Bible says is sometimes a merging of what is there in black and white and how one’s faith tradition has come to understand it. And that merger is often seamless, so much so that most readers are not even aware of it. Biblical writers were not immune to this phenomenon …”13 This again demonstrates the fluid interplay between tradition and text during this period and how these traditions can and did even escape normative Jewish literary boundaries even prior to their New Testament incorporation.

These examples provide an intriguing window into the formation of biblical literature and traditions. Comparing these traditions across texts reveals processes of development as ideas grew and details expanded through interpretation. Later biblical authors worked within an ecosystem of biblical interpretation that shaped how they composed and understood earlier scriptural traditions. Paying attention to these complex intertextual relationships demonstrates that written texts and the traditions they contain have their own developmental histories. While the dating of compositions is important, we must also appreciate how biblical literature springs from a stream of continuously evolving tradition and isn’t quite so easily fixed.

Kugel, James L. The Bible as it Was (pp. 342-343) Harvard University Press, 1998

Chilton, Bruce "From Prophecy to Testament" in Evans, Craig A. (ed.) From Prophecy to Testament: The Function of the Old Testament in the New (pp. 23-43) Hendrickson Publishers, 2004

Evans, Craig A. Ancient Texts for New Testament Studies: A Guide to the Background Literature (p. 71) Hendrickson Publishers, 2005

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. First Corinthians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (p. 546) Yale University Press, 2008

Smith, Mark S. and Elizabeth M. Bloch-Smith Death and Afterlife in Ugarit and Israel Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 108, 1988

Cook, John G. Raised on the Third Day According to the Scriptures: Hosea 6:2 in Jewish Tradition (pp. 188-211) Brill, 2019

Enns, Peter The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say about Human Origins (pp. 114-115) Brazos Press, 2012